Channeling the Legacy of AIDS Activism into a Broader Movement for Sexual Justice (2019)

For the 50th anniversary of Stonewall, CHLP Staff Attorneys Jada Hicks and Jacob Schneider write for a special edition of Outward at Slate.com exploring the many legacies that shape queer life today. Their essay suggests that queer communities can honor and channel the legacy of the 80s and 90s AIDS activism by building a broader movement for sexual justice.

---

Carrying the Legacy of AIDS Activism Forward

The end of HIV transmission is within reach. But that’s just the beginning of what the movement could accomplish.

By Jada Hicks and Jacob Schneider

Read this article at Slate.com

This piece is part of the Legacies issue, a special Pride Month series from Outward, Slate’s home for coverage of LGBTQ life, thought, and culture. Read an introduction to the issue here.

What would a world with little or no HIV transmission mean for the AIDS justice movement that many in the LGBTQ community have spent the past three decades building?

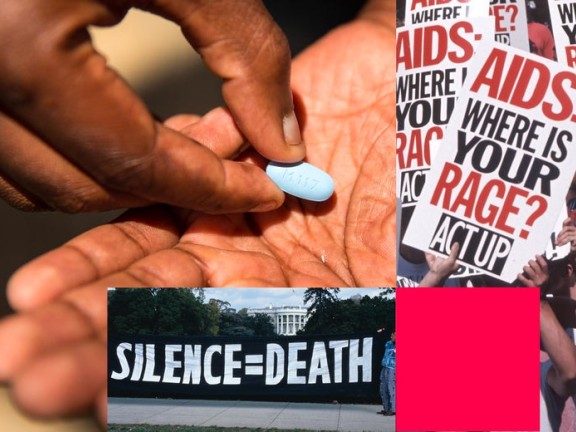

The question might have been unimaginable before 2014. That’s when Truvada, a pre-exposure prophylaxis (or PrEP) drug that when taken daily reduces the risk of acquiring HIV through unprotected sex to nearly zero, became widely available. More recently, that innovation has been joined by the growing understanding that a person on effective treatment cannot transmit the virus (generating the slogan “undetectable = untransmittable” or U=U), allowing people living with HIV to shed the fear that they pose a risk, however small, to a partner.

These developments have led to a great deal of optimism within the HIV treatment community. Many believe that if we can make PrEP and effective treatment widely accessible, we can look forward to a future without HIV transmission, and a near one at that. Even the Trump administration, which recently announced a plan to end HIV transmission by 2030, shares this vision—though to date the federal government has failed to match that ambitious goal with a commensurate commitment of resources.

This long-awaited milestone, should we reach it, would represent the culmination of a great deal of work by AIDS activists—led by groups such as ACT UP and TAG (Treatment Action Group)—who, early on in the epidemic, demanded a seat at the policymaking table, shaping public health approaches in concert with the lived realities of the communities affected by HIV. In doing so, they took on not only an unprecedented medical epidemic but also the demonization of gay sex, as exemplified by centuries of anti-sodomy laws, discriminatory policing, and cultural stigma. The idea that we can actually see an end of HIV transmission on the horizon represents a triumph for that movement. It also presents an opportunity to think about the road ahead.

While it might be tempting to celebrate this success as an end unto itself, to truly honor the legacy of AIDS activism, queer communities should take its lessons and energies and build a broader movement for sexual justice. One way of doing this is to channel our advocacy into other areas in which outdated prejudices and ignorance have and continue to fuel legislation that criminalizes the sexual lives of others. That includes challenging laws that continue to criminalize HIV exposure as well as engaging in areas that some might view as far afield from LGBTQ issues—from sexual health literacy access to sex work and even sex offender registries —but are actually of a piece with our values and experience.

It is surprising that the issue of HIV criminalization is not widely known or discussed in many sectors of the queer community, given the fact that 34 states and several U.S. territories still have criminal laws that punish exposure to HIV or dramatically increase sentences for crimes when the defendant—whether a sex worker or a person who injects drugs—is living with HIV. Most of these statutes do not require any proof that a person intended to transmit HIV or even did anything that created a measurable risk of transmission.

These laws are out of touch with contemporary understandings of the routes and risks of HIV transmission, and they conflict with the long-standing legal principle that we only punish those who act with the intent to do harm to another. Available data on whom these laws target show that they are enforced against those with the least amount of political capital—black men and women, sex workers, people who inject drugs—and in the absence of any evidence that they actually do anything to reduce risky behavior or HIV transmission. These laws draw not only on the anti–gay sex stigma of HIV but also on cultural tropes about the sexual danger of black men and women and other marginalized groups.

Challenging the anti–gay sex stigma of HIV criminalization laws is essential, but doing that alone stops short of realizing a broader vision of sexual justice that flows directly from the AIDS activism of the 1980s and 1990s.

Having seen the myriad ways that stigma, discrimination, and sexphobia fueled misguided responses to HIV—including criminalization laws—we should prioritize arming members of our community with scientifically accurate information. That starts with framing comprehensive sexual health literacy that incorporates the needs of queer youth as a fundamental public health issue. Indeed, one of the basic public health lessons of HIV is that we can be confident that it will not be the last sexually transmitted epidemic, and it’s possible that the next epidemic will come from a familiar disease. In fact, one result of the proliferation of PrEP is that many gay men have stopped using condoms; while there is no direct evidence of a causal relationship, rates of other sexually transmitted infections have soared. While those diseases are largely treatable now, we likely will soon see more drug-resistant strains of infections like gonorrhea in the U.S., and if left untreated they can wreak serious havoc.

The queer community should be at the forefront of a coordinated effort to push back against laws that punish people based on their HIV status or sexual lives. Though we already know from HIV that criminal punishment is not an effective public health response, we still see efforts to do just that with drug use through injection, needle sharing, sex work, and the growing spread of viral hepatitis, which has been fueled by the opioid epidemic.

More than anything, having experienced the ways that access to effective and appropriate HIV care—such as PrEP—has been politicized to the detriment of the most disenfranchised members of our community, we should recognize that the same weaponization of health care is currently happening to women—including queer women in states passing abortion and contraception bans. Just like laws criminalizing gay sex, this new wave of anti-abortion laws permits religious and moral objections to outweigh an individual’s own personal sexual and reproductive health choices. Women were on the front lines of the AIDS movement in the 1980s and ’90s, and it’s now time for the queer community to stand with them.

The advent of safer sex through science is an opportunity to reflect on a major success of the past three decades of AIDS activism, but we know that the story of legal and social discrimination against people based on their identity and sexual choices does not begin and end with HIV. It is incumbent upon us to honor the legacy of AIDS activism by spearheading a broader movement for sexual justice going forward.