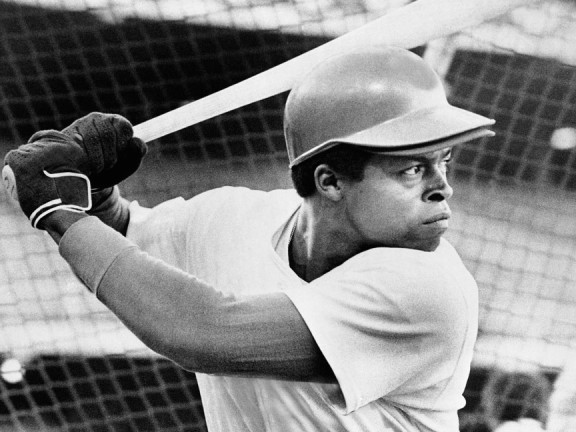

Honoring Our Heroes: Glenn Burke

Major League Baseball is honoring Glenn Burke as a pioneer: the first player to come out as gay. Burke, an African-American man, publicly announced he was gay in 1982, two years after he had left the league, although he reportedly was out to some teammates and managers long before that. In his autobiography, Burke said he had felt forced to choose between his identity and the sport he loved. Thirteen years after leaving baseball, in 1995, he died of AIDS. Burke’s story is an apt illustration of the common threads binding homophobia, HIV stigma, and racism.

In sizing up the state of gay visibility in sports and baseball in particular, commentators overlook the significance of the fact that the first national face of a gay major league baseball player was an African-American man with HIV whose identity struggles likely had much to do with his reliance on drugs and eventual homelessness -- all while living in the heart of the gay community that once celebrated, and now again, embraces him.

Today, as Burke is honored for his contributions to the movement for LGBT equality, many queer and HIV-affected people -- particularly people of color, immigrants, and those with limited resources -- continue to experience the type of oppression and discrimination that Burke faced decades ago.

As LGBT organizations celebrate Burke’s well-deserved honor, we challenge the movement for LGBT equality to recognize the courage of queer people of color and HIV-affected folks who openly claim their identities at work -- in construction sites, factories, and minimum wage jobs -- and in other settings, including health care settings, where homophobia, HIV phobia, and racism are too often accommodated rather than challenged.

These are the same people who tend to be targeted when health care providers, neighbors, friends or disappointed lovers turn to the criminal law to control them. In 32 states, HIV is criminalized based on misconceptions about the routes, risks, and consequences of HIV transmission.

If Burke were alive today, he could be at risk of arrest based on little more than his HIV status and homelessness. Hundreds remain behind bars, some classified as sex offenders, and many are facing prosecution at this very moment. The criminalization of people of color, queer folks, and those living with HIV warrants broader, more aggressive action.

If you believe, as Bayard Rustin did, that "the proof that one truly believes is in action," one way to honor Burke’s memory as a pioneer is to take action on behalf of those in our communities who are still being left behind. You can sign the National Consensus Statement Against HIV Criminalization, get involved with the Positive Justice Project (PJP) and join local activists who are working at the state level as part of a national campaign to end HIV criminalization. You can be a part of a PJP state working group and help plan actions to end HIV criminalization in your home state.

To join or start a Positive Justice Project state working group or to sign the National Consensus Statement Against HIV Criminalization, contact Tosh Anderson (programassociate@