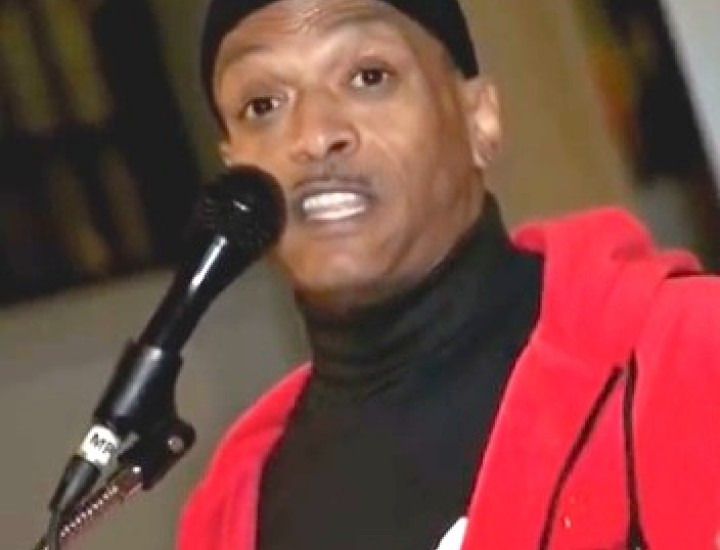

Unsung Heroes: Stephen R. Scarborough, Criminal Defense Attorney

Stephen R. Scarborough is a criminal defense attorney based in Atlanta, GA, specializing in serious felony cases in both state and federal courts. He has been an advisor on criminal justice issues to CHLP staff and others for years. As is often the case, he is both very talented and very humble about his talents. CHLP Communications Consultant Andrea Sears interviewed Scarborough about his experience as a litigator on HIV criminalization cases.

Andrea Sears Stephen could you begin by saying how you first became involved in HIV criminalization litigation?

Stephen Scarborough In 1997, I became the first staff attorney at the southern regional office of Lambda Legal and was doing some work for the HIV Project, under Catherine Hanssens actually. She was the director of the HIV Project at the time. I didn’t have much direct involvement there in any particular litigation, but got into some of the policy work and that’s how I started.

AS What kinds of cases have you worked on over the years?

SS I’ve had a few cases of failure to disclose or alleged failure to disclose that have led to felony charges. I’ve tried to keep abreast of developments in them and tried to consult with lawyers who are handling them whenever that help is welcome. What I find much more frequently is that I’ll have an HIV related issue in a criminal case, often having to do with either an alleged sex crime or some aspect of sentencing for another crime where there’s usually an unwarranted fear of transmission. I am often in the position of trying to explain to courts or even to prosecutors that those concerns are unfounded or overblown.

AS What are some of the common elements that you’ve found among the defendants that you’ve worked with? Is there anything beyond HIV status? Sexual orientation, gender, whether or not HIV was actually transmitted, race or economic status?

SS It’s really run the gamut. I’ve had defendants in some federal criminal cases who were quite well off socio-economically. I don’t know how good a sample my client base is necessarily, but I think failure to disclose tends to be charged more in cases where the person is of a lower socio-economic status. I also have done a little bit of research about who’s been affected by these charges in the state where I currently practice, which is Georgia. And it appears that of the total defendants about two-thirds are African American, including a number of women whose criminal records suggest that they’ve been involved in sex work.

AS Is violation of an HIV statute the only charge in most of these cases or is it part of a broader indictment? Are HIV charges used as bargaining chips in plea deals?

SS I see stand-alone cases, actually, especially in some counties of Georgia where prosecutors can be especially enamored of this kind of prosecution. I guess the only exception that I see frequently is when there is a prostitution scenario. They’ve got what would simply be a misdemeanor charge and then the failure to disclose, which is called reckless conduct in Georgia, is charged and of course that creates the bigger problem for that person because it’s a felony.

AS What kind of advice do you give your clients on first meeting if there is an HIV charge involved, especially if it’s a related crime such as failure to disclose in a prostitution arrest?

SS Really what I want to get is knowledge of any communications that they had with anybody about their status. And I like to make sure those are preserved and not lost. Sometimes it’s a matter of text messages or other communications that could be helpful because sometimes the charge of failure to disclose is simply baseless. I also tend to advise people about their right to protect the privacy of their health information because I’ve actually had some cases where medical practices have disclosed to requesting law enforcement agents without requiring them to jump through all the appropriate legal hoops before getting that information. So I want to make sure people are aware that they have rights in that regard and they want to remind their physician of those rights.

And then there’s simply the basic thing which is don’t talk to anyone about this because these can be the sorts of charges that are often invested with interpersonal drama. It’s helpful for information to be contained rather than different accounts of information given to different players.

AS What are the medical privacy concerns in HIV criminalization cases? What kind of medical privacy rights do exist and where does law enforcement have latitude?

SS Well, in Georgia, there is a statute protecting the confidentiality of what they call “AIDS confidential information”. It’s an old term. But there are many, many exemptions from the privacy rule. Some of them are pretty familiar, similar to the types of exceptions you have in HIPAA for insurance or whatever. But unfortunately Georgia is a state where any time there is a charge of HIV reckless conduct, that is a per se exception to privacy and the prosecution can obtain medical records simply on the basis of having charged that crime. There’s a further provision that allows a court to authorize disclosure but there’s supposed to be a hearing in the judge’s chambers away from the public courtroom to determine whether there’s a compelling need. And I guess the risk there is that a compelling need might be found too rapidly or too easily based on a particular judge’s view, really an outdated view, that a person is more infectious than they are.

AS What role does actual transmission play? Have there been cases that you have worked on where there was no transmission? Disclosure cases, for example, often come down to a matter of ‘he said – she said’. What role does the actual danger of transmission and actual transmission play in prosecutions?

SS I’ve been involved in very, very few cases where there’s an actual transmission. I’ve never handled one of those directly. Almost the entire concern with these cases can be summarized as just inaccurate perceptions of transmissibility. And so there is a possible judicial assumption that’s very uninformed that if there’s been sexual contact there’s a high risk of infection.

And certainly another assumption that’s often made is that if a complaining witness has HIV or acquires it they must have gotten it from the defendant. And of course that’s not necessarily the case. In fact a complaining person or a complaining witness who has been engaging in behavior that might lead to transmission may tend to do that with some frequency.

So there’s often a need to really tamp down the hysteria or sensationalistic reporting about a case because you’ll have the sort of set up that newspapers really love which is that there’s some person who’s been wronged or betrayed and infected by a partner or something like that. I’m not inferring that it never, ever happens but it sure is rare. And you would think from reading some of the coverage of these things that it’s a common and likely occurrence.

AS Some HIV criminalization laws are aimed at behavior that is extremely unlikely to have a risk of transmitting HIV, spitting or biting for example. Is that an issue that can be raised at trial, that the law itself is based on a fiction?

SS Well, it’s tough to do that sometimes because the constitutional power to criminalize, or to operate in the area of public health is there. It’s hard to argue that a state or an authority doesn’t have the ability constitutionally to legislate in that area. And so it really comes down to how the statute is fashioned because if you indeed have a statute that lists certain enumerated acts and says you’re guilty if you do this and you don’t disclose, then a prosecutor can object on relevance grounds if you try to get in any information about real transmission rates on the grounds that it doesn’t have anything to do with what were the elements of the case.

That doesn’t mean that information is irrelevant entirely because of course you want to get that information across to prosecutors when you’re trying to plea bargain or get a case dismissed. But it often can be a problem because our instinct would be to put on an expert and to demonstrate through science that infection is not likely to happen or there’s virtually no chance of its happening. But if you’re operating with a statute that says if you have oral sex and don’t tell somebody you’re positive that’s all it takes, then that kind of evidence can sometimes be ruled inadmissible.

AS Sometimes it seems laws like that would practically allow prosecution for performing voodoo or witchcraft if the actual ability to transmit is practically nonexistent.

SS A lot of these cases will be prosecuted as aggravated assault with intent to murder or attempted murder or something ludicrous like that. It will be like an inmate who spits on a guard. And sometimes there’ll be some unhelpful utterance like the prisoner says, “I’ve got AIDS and now you’ve got it,” or something like that. What happens sometimes is that courts look only to the intent of the person, rather than the possibility of it happening. It’s kind of like me taking a feather and hitting you on the head with it and saying, ”I’m going to kill you with this feather,” and then being convicted of attempted murder because that’s what was in my head, even though it’s utterly impossible for me to kill you by hitting you with a feather. So there ought to be, and in some jurisdictions there is, a sort of rule of reason that comes into play. But when that rule is not applied, as in some Georgia cases, you can get these really stupid outcomes.

AS What’s the role of medical testimony in these proceedings? Do the defense and the prosecution both present expert witnesses? How much does the actual transmissibility of HIV come into play?

SS Well I haven’t seen the prosecution put on a witness ever for one of these things. And that’s usually because actual information about likelihood of transmission is not going to help them. But I’ve had respectful receptions to experts that I’ve put on. I’ve had some federal judges express appreciation for what they’ve learned from some of these witnesses. But the problem is they keep falling into this notion of, “Ok, you’ve just proved to me that it’s an infinitesimal risk but it’s still not a zero risk. And unless you can say it’s an absolute total impossibility and its zero-point-zero risk, then it’s still something.” It’s not very rational thinking when you’re talking especially about sentencing because of course we all take hundreds of risks a day just in going about our daily activities that are non-zero risk.

I once I reminded a judge that if he had driven to court that day he had assumed a much larger risk than any risk my client had put anyone to. And the judge was thoughtful about it and said, “Well I now understand that you’re right about that”, but then he still took it into account as an aggravating factor that my client hadn’t disclosed. And he had this sort of notion that it’s just some obligation that people should always disclose.

AS What about mitigation? How much does it count if a defendant has taken steps like being on medication, reducing their viral load to virtually undetectable levels, using barrier protection like a condom? Does this help?

SS It often does not. I think that when a case is being negotiated or when argument is being done outside of court, usually that’s the most effective time to make sure that that information is understood by the prosecution. But I regrettably don’t see a lot of leniency coming out of facts like that. And I think it’s really just a problem of judges being stuck in 1985 in terms of what knowledge there is about the epidemic or about the health issues.

AS Some laws require intent to transmit HIV. How do they establish intent?

SS Well, you can have utterances like the unfortunate one that I mentioned with the prisoner. Or it’s going to be circumstantial, usually. It’s rare but I think there are cases where people write notes and say, “I’ve done this to you”. It’s going to be a matter of circumstantial proof as to the particulars of the act. But those statutes are at least better than the ones that don’t require intent because a prosecutor has to show beyond a reasonable doubt that a criminal wanted to infect someone. It can’t just be something that makes a juror of a judge wonder whether it might have been intentional. It has to be established really quite plainly that that’s what the person was trying to do.

AS Does the same apply for consent? Consent can be argued, whether it was offered or given.

SS Yeah I think if consent is informed and voluntary that suggests that disclosure happened and that’s helpful. The problem is sometimes it can be difficult as a practical matter to prove that, because of course in a criminal case the defendant doesn’t have to put up any evidence and that’s their right. But as a practical matter the accused person may be the only one with knowledge that the other person consented. And so it can kind of force you onto the witness stand when you otherwise wouldn’t have had to do that or to present any evidence. And that can be tough for example if someone has other difficulties in their past that they can be questioned about. Sometimes that can be hazardous.

AS So it sounds like the burden is often on the defense to prove that the defendant is not guilty rather than on the prosecution to prove that the defendant is guilty.

SS Yeah that is a real problem because the most common defense is disclosure. And so what the jury wants to know is, “okay if you disclosed, where’s the proof of it?” And so again that forces a defendant to put up evidence. And it’s also just hard as a practical matter because I’m not in the habit of writing contracts with my partners before I engage in sex with them. So very often there may not be contemporaneous proof that there was disclosure made.

AS In HIV criminalization cases is it preferable to have a jury or a nonjury trial, or does it depend on the particular case?

SS I think it depends. It will depend of the judge. If you’ve got a judge who is open to accurate information about what the actual likely harm could be, then it may be one of those cases where it’s good to do a bench trial. You want to really vet your judge because some judges in any jurisdiction play it to sort of pander to community prejudices.

AS What kind of advice would you give to attorneys who are assigned as public defenders or hired to work on an HIV criminalization case?

SS I would say take advantage of the available resources. Like anything you have to educate yourself about it. You can be a very intelligent, capable professional person and not know much about HIV so it’s important to get educated about it. And organizations like the Center for HIV Law and Policy have materials that are readily available. I just think it’s critical to not come into defending a case with the same sorts of ignorance or wrong assumptions that others may have.

AS And over your years of experience working on cases like this are you seeing any trends? Are you seeing more prosecutions coming up? Are they becoming less frequent? Is public knowledge about the nature, treatability and risk of transmission having an impact on this problem of criminalization?

SS It’s hard to say. I think it probably depends even on a county-by-county basis. Georgia has an exorbitant number of counties, there are 159 in the state, and so there can be a decent number of cases each year but there aren’t many in any given locality in a given year. So it’s really hard to perceive trends and it would be interesting to know if there could be any rigorous statistical analysis done on that sort of thing. I think it largely depends on the local authority.

AS Is there anything else you think is important about HIV litigation that we haven’t talked about?

SS I think the recent studies that show a zero or near zero transmission rate for people who are doing well on anti-retroviral therapy are going to continue to push these issues. Interesting times are sure to come but there’s probably going to continue to be some push back against the very idea that there’s no risk at all.