Times-Picayune: HIV is no longer a death sentence. But under Louisiana law, it can be a prison sentence

This article in the Times-Picayune looks at HIV criminalization laws in Louisiana. It interviews Robert Suttle, who was accused of intentional expsoure of HIV by a former partner, served six months hard labor, and was required to register as a sex offender. CHLP Executive Director S. Mandisa Moore-O'Neal spoke about the ongoing work to reform the HIV criminalization laws in Louisiana. “Our coalition tried unsuccessfully to get the lawmakers to modernize it in the way that we knew, based on data and based on experience, was really necessary,” said Mandisa Moore-O’Neal, co-founder of the Louisiana Coalition on Criminalization and Health. “Unfortunately, our state has not done the work of modernizing its laws in alignment with science.”

Read the article below or online at NOLA.com.

-------

HIV is no longer a death sentence. But under Louisiana law, it can be a prison sentence.

By Emily Woodruff | Staff Writer

Oct 3, 2022 - 4:02 am

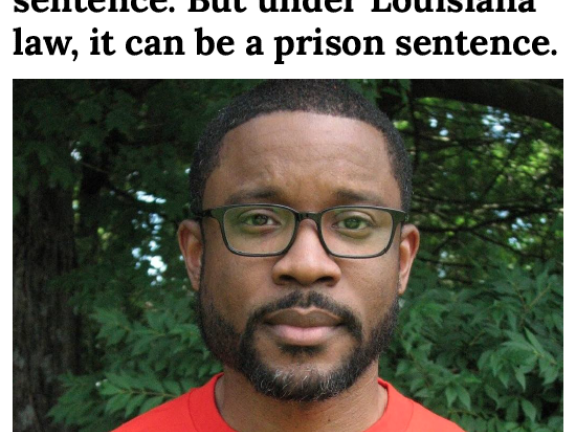

Robert Suttle thought enlisting in the Air Force after college in 2003 would give his life structure. Instead, the enlistment process gave the Shreveport resident a life-changing diagnosis: He was HIV positive at age 24.

Suttle was in shock. He didn’t know anyone with HIV. Even as a young gay Black man in the South, he wasn’t aware he was at risk. No one talked about HIV where he was from.

But because it was 2003, he was able to get access to drugs that prevented the debilitating symptoms and painful deaths of the 1980s and early 1990s. For him, HIV was not the death sentence it once was. But under Louisiana law, it would wind up being a prison sentence.

In 1987, Louisiana was one of the first states to enact a law that makes it a felony for a person who knows of their positive HIV status to expose another through any means of contact without the knowledge of the other person.

Legislators believed it would reduce the spread of a virus that was poorly understood and much feared. But now, in an age when HIV is a treatable disease, advocates say it has instead further penalized and stigmatized people living with HIV.

In Louisiana, spitting can be a felony

Since 2011, at least 176 people in Louisiana have interacted with the criminal legal system because of HIV crime allegations, according to a new report by the Williams Institute at UCLA School of Law, which studies the impact ofthese laws. For the majority of those people —80% — an HIV-related crime was their only alleged offense.

Louisiana’s law doesn’t require actual transmission of the virus, the intent to transmit, or even consider whether transmission was scientifically possible to convict. The law criminalizes non-sexual behaviors such as spitting and biting, which are not transmission routes.

And the law in Louisiana is disproportionately enforced based on race and sex. Black men make up 15% of the population in this state and44% of those living with HIV, but 91% of the arrests for allegations related to HIV crimes, according to an analysis of law enforcement incident-level data and the state’s sex offender registry.

The maximum penalty is 10 years in prison and a $5,000 fine, with an additional year and thousand dollars tacked on if a police officer is involved. While many states have some sort of HIV criminalization law, Louisiana is one of a handful of states that also requires a person to register as a sex offender for 15 years if convicted of a crime related to HIV, said Nathan Cisneros, HIV Criminalization Analyst at the Williams Institute. As a result, people wind up labeled as sex offenders for behavior that cannot transmit HIV.

“For example, spitting, biting, throwing urine or other bodily fluids on somebody — things that we wouldn't expect would result in you winding up on the sex offender registry,” said Cisneros. “Nonetheless, Louisiana requires that you go on the sex offender registry."

The HIV outlook has changed dramatically over the last 40 years. Medications allow for an undetectable viral load of HIV, meaning infected people who take a daily pill cannot transmit the virus, and those more at risk can take a pre-exposure prophylaxis (or PrEP) pill or shot to prevent transmission. But the rate of arrests is not going down. The 176 people identified in the

analysis is likely an undercount, because not every parish reports to the state’s incident system.

“That's the absolute minimum basement floor,” said Cisneros. “What we observed is that people are still being arrested and cited in 2022. And we think that as more law enforcement agencies participate, we'll actually see that number go up.”

The arrest

Suttle was working as an assistant law clerk at the Second Circuit Court of Appeal in Shreveport when officers arrived to arrest him in front of his colleagues in 2008. They spent months investigating him after a former partner from a casual relationship that turned sour accused him of not disclosing his HIV status. Suttle says he did disclose his diagnosis, but that didn’t make a difference. At that point, it was his word against his former partner’s.

“What I've learned is that as according to these laws and how things are applied, it really doesn't matter whether a person has disclosed or not,” said Suttle. “What this is really about is identifying people who are infected with HIV.”

He lost his job and moved back home with his mother and grandmother. When he walked into the house after his arrest, his mother had two words for him: “We know.”

Rather than risk a maximum sentence, he took a plea deal. He received two years of probation. He had to register as a sex offender, which meant mailing notification cards to all the neighbors in the area where he lived his whole life.

“It's my church and family and people that know me,” said Suttle. “They lived where I lived.”

He paid to put his picture in the newspaper in the sex offender section as required by law. His driver's license was stamped with a bright red SEX OFFENDER status right under his picture. Fees from the court and attorney were piling up. He was trying to do everything by the book, seeing his probation officer regularly so he could start to put it behind him. But he felt a pervading sense of disbelief over how his life became derailed.

“All I could do was just show up when I'm supposed to show up and just wait for them to tell me what they're going to do,” said Suttle. A deep pain his stomach, the kind that made him want to curl up in a ball, was ever-present.

About a year into his probation, he was told that the court had made a mistake — that the law stipulated hard labor for his crime. Before a judge in Caddo Parish in 2010, he repeated, “Yessir,” when the judge asked him if he under stoodhis new sentence. He pled guilty as a necessity, so the ordeal would end.

Forty-five days later, he turned himself for a six-month sentence at Elayn Hunt Correctional Center.

Modernizing HIV crime laws

States have moved to modernize HIV crime laws in recent years. Texas repealed its law in1994. Illinois repealed in 2021. Eight other states have modernized their laws since 2014, taking actions such as requiring transmission or intent for a conviction and reducing the penalty from a felony to a misdemeanor.

In 2018, a bill was brought forth by Rep. Edmond Jordan, D-Baton Rouge. The statute was amended to replace the inaccurate “AIDS virus” language with “human immunodeficiency virus.” The bill removed specific references to spitting or biting, but left broad language referring to “any means” of transmission. Rather than restricting criminal liability, the 2018revision expanded it, advocates said.

“Our coalition tried unsuccessfully to get the lawmakers to modernize it in the way that we knew, based on data and based on experience, was really necessary,” said Mandisa Moore-O’Neal, co-founder of the Louisiana Coalition on Criminalization and Health. “Unfortunately, our state has not done the work of modernizing its laws in alignment with science.”

When the surface-level changes were proposed to the law, there was no political will to make more modifications, and there hasn't been since. Moore-O'Neal is hopeful more education efforts by the coalition will help sway the public and lawmakers in the future.

The coalition takes the stance that a good law should reflect intent to transmit and proof of actual transmission of the virus. Moore-O’Neal, who is now the executive director at the Center for HIV Law and Policy, has seen how Louisiana’s HIV criminalization laws have impacted one family she knows after a father was required to register as a sex offender.

“Their family can't even go into the library, because he was legally barred,” said Moore-O’Neal. “He can’t even go to pick up his own children from school.”

'There's still the residue of it'

In prison, Suttle watched summer turn to fall. Weekly, he got on a bus with every other person with some sort of chronic disease for treatment. He wondered what he’d be doing if he was home.

“I needed to get back to my grandmother,” said Suttle. “I needed to get back to my family and I needed to get back to my life. This wasn’t supposed to happen, at least in my plans for myself.”

After he got out of prison in 2011, he worked briefly in social services, where he made sure to tell young Black men with HIV about the ways they could be criminalized. In trying to come to terms with what happened to him, he started researching HIV crime laws and reaching out to advocates in the field. He was invited to Switzerland to speak about his experience, then Norway. A year later, he moved to New York City and became a founding member of The Sero Project, a national network of activists who aim to repeal HIV criminalization laws.

Staying in Louisiana wasn’t really an option. The sex offender status made it difficult to find work and a place to live.

“Even now, it's like, 'Did that actually happen?'” said Suttle. “There's still the residue of it, and like, oh my God, I actually went through that.”

Suttle got a call last week on behalf of a man sitting in jail in Calcasieu Parish on HIV criminalization charges. It’s a reminder that what happened to him in Louisiana is still happening over a decade later.

“Louisiana is the incarceration capital of the world,” said Suttle, now 43. “And they're definitely living up to it by using HIV as another way ... to prosecute and criminalize Black people.”