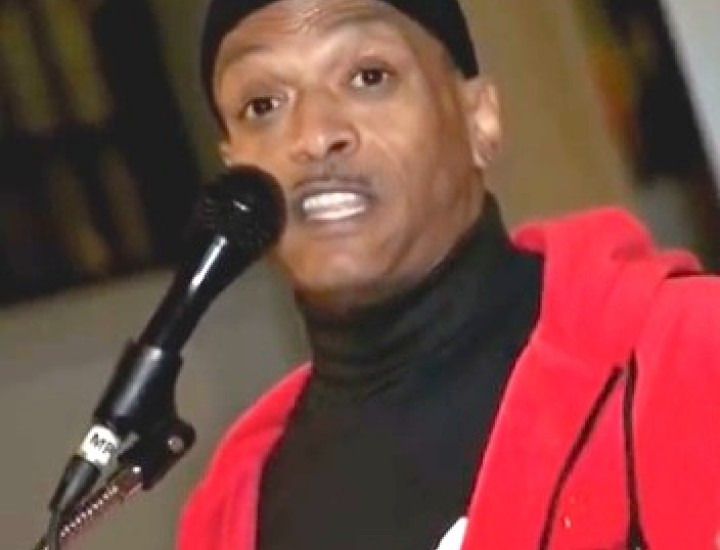

Unsung Heroes: Eric Evans, HIV Advocate, Shreveport, Louisiana

Eric Evans is the vice-chair of the Louisiana AIDS Advocacy Network and the Advocacy Coordinator at the Philadelphia Center in Shreveport, Louisiana.

He was interviewed by CHLP’s Andrea Sears

Andrea Sears What is the Philadelphia Center?

Eric Evans The Philadelphia Center is northwest Louisiana’s HIV resource center. We deal primarily with client management and people who are living with HIV. Officially, it’s been around since 1990, but it’s actually been around longer than that. We do case management, prevention, testing, and advocacy thanks to a grant from the Elton John AIDS Foundation.

Through a federal grant that the state administers we have also recently started what’s called a wellness center where we actually open a small clinic twice a month that allows us to test gay, bi, transgender folks not just for HIV, but also for STIs and to give them other health evaluations at no cost to them.

We also have a program for young women called Sisters Informing, Healing, Living & Empowering (SIHLE). And we provide housing. We have what’s called Mercy Center, which is housing for people who otherwise would be homeless. So it’s a wide spectrum organization and it’s the only one of its kind in northwest Louisiana.

AS The HIV criminalization law in Louisiana follows the pattern of laws in many other states in that it criminalizes behaviors that have little or no risk of transmitting HIV. What’s the background of this law?

EE The law was originally written back in 1987, as it was in many other states around the country, when there were still a lot of questions and concerns about what exactly were the causes of HIV and how it was spread. So there wasn’t a lot of foresight or science to call on at the time they passed these laws.

AS A great deal has been learned about the diagnosis, treatment and spread of HIV since then. Why hasn’t the law kept up with the science?

EE A lot of laws get put on the books that are just forgotten and they just kind of sit there. I wish that were true with the HIV criminalization laws, but I think that sometimes these laws are kind of used as add-ons, I call them, to other charges. Say for example if a sex worker is arrested for prostitution and they disclose their status then they can tag on possible HIV exposure charges. That’s one of the scenarios.

AS What’s been the pattern of enforcement or has there been enforcement of this statute? Are people being imprisoned?

EE Law enforcement will many times tag on an HIV criminalization charge. Then you have situations where somebody accuses another person. A case in point, somebody in a relationship, even if they disclose their status, if the relationship goes bad, one can accuse the other of having infected him or her, or having exposed them to HIV. And that’s a key word. They use the word “expose” very loosely. The statute even says that spitting is still considered a form of exposure to HIV, and we all know it is not.

AS Have there been many of those accusations from a failed relationship in Louisiana?

EE Actually that’s where we’ve had the most trouble with this particular law. It has been used more often than not successfully to prosecute somebody in a relationship situation.

AS Is the HIV criminalization law as it’s enforced in Louisiana a racial justice issue?

EE Yes. I think it crosses the entire spectrum because as we know here in Louisiana our greatest number of new HIV cases per capita are young African American men and women. So that alone suggests that there’s going to be a higher possibility of a young African American man who has sex with men falling into this situation and running up against this law.

AS The law in Louisiana specifies that there must be intent to spread HIV for someone to be convicted. If you don’t know your status, you can’t intend to infect someone so does the law create fear of testing?

EE I think this is one of the unfortunate justifications for not getting tested. But a lot of young people just do not know that the law even exists. There are multiple reasons people avoid getting tested and there always have been. Stigma still exists around getting tested and finding out that you’re HIV positive.

AS A lot of the effort toward reforming or repealing HIV criminalization laws depends on raising public awareness and combatting stigma. What’s the situation in Louisiana? What’s the level of public awareness and what obstacles do you face in raising public awareness that these laws don’t fit the current science of HIV?

EE Well doing what I do now, which is doing interviews, and speaking publicly to organizations and support groups, I have printed material that I hand out at public functions. It’s a grassroots awareness campaign because, honestly, even when I moved here I didn’t even realize they had such a law here until I went to work for the Philadelphia Center. And unfortunately there are a lot of young people who don’t know this law exists and don’t understand the gravity of this law if it should become an unfortunate part of their lives.

So we speak out to the colleges in this part of the country. We’ve also started working with the Louisiana Office of Public Health in conjunction with their STI (sexually transmitted infections) program to bring more awareness about the importance of knowing their status because I think that the basis for a lot of stigma is fear of getting tested. That’s something that we still have to get resolved. People should not be afraid of getting tested.

AS What kind of efforts are underway in Louisiana right now to change this law?

EE First, we’ve had to start making people more and more aware. To do that a lot of times it’s a case where a person’s been arrested unjustly, and letting the prosecuting attorney know that they should revisit the law. But it’s also been really important for us to start building a coalition with other organizations, including faith-based organizations, across the state to start focusing on what needs to be done.

In Louisiana, the climate is not real good when it comes to trying to reform a bad law. We’re hoping to be able to get this law revised, but it’s going to take a huge effort. We’re just trying right now to bring more awareness because it may take many years for legislation to get passed. But the law as it is written is antiquated; it’s out dated and needs to be revised.

AS And who are the people behind the efforts in Louisiana to reform or repeal this law?

EE The Louisiana AIDS Advocacy Network (LAAN) has been actively working on this law. A lot of what we do is in conjunction with AIDS Law Louisiana, which is a not-for-profit legal organization here. They’ll take on many cases. And then we have other community-based organizations throughout the state, including an organization that deals with mass incarcerations. There’s just a long list of organizations that we have been in contact with and working with to get a very wide base of support for getting this law reformed. Any organization that we can get assistance from or that has a situation that is going to help us improve the law, we’re more than happy to have them come on board with us. Just contact me at LAAN.

We’ve been very proud to work with several national organizations and I think that is going to be another one of the big factors that is going to help us make this HIV criminalization law revision less challenging to deal with because we have national organizations that see what’s going on, see what the need is, and are willing to help us out.

This is going to be literally a community effort, locally, statewide and nationally with everybody pitching in to try to make our society one that is more just and understanding of where we are with HIV today versus back thirty-some-odd years ago.

CHLP’s Unsung Heroes is a series of portraits included in The Fine Print blog of individuals who are contributing mightily, without fanfare, to keep our issues, needed agencies, and members of our communities alive.