TheBodyPro: We Can Stop the Attacks on Bodily Autonomy and Health Privacy

To highlight the themes of bodily autonomy, health privacy, and the Denver Principles, CHLP Policy & Advocacy Manager Amir Sadeghi wrote this #HIVTestingDay reflection for TheBodyPro. He urges more level setting with medical allies, with public health officials, about the legacy and reality of criminalization, mass incarceration, and the roots of state violence targeting our communities. And that even simply considering molecular HIV surveillance in the real context of HIV criminal legal enforcement represents a dangerous subversion of public health, something that should be about protecting communities.

Read below or at TheBodyPro.

We Can Stop the Attacks on Bodily Autonomy and Health Privacy

Amir Sadeghi

June 27, 2023

Forty years ago this month, a manifesto written at a conference in Denver, Colorado, changed HIV/AIDS activism forever. That manifesto, The Denver Principles, lives on with a lasting impact as an assertion about the fundamental rights of people living with HIV, but it also carves out universal rights that benefit everyone. The rights to medical confidentiality and privacy, quality medical treatment without discrimination, and bodily autonomy are among those chosen by about a dozen gay men, at the time living with AIDS.

Nearly 500 anti-LGBTQ bills have been introduced across the country this year alone. Violence from white nationalists, far-right activists, and police deservingly receive the most attention, even while others are conspiring to undermine the rights of marginalized Black and Brown, queer and trans people affected by HIV. Pharmaceutical companies fiercely defend their profits gained during the epidemic and raise more barriers to access PrEP like invasive and unnecessary databases to monitor low-income users. But big pharma is not alone in jeopardizing the lives and dignity of the people most affected by HIV and health injustice.

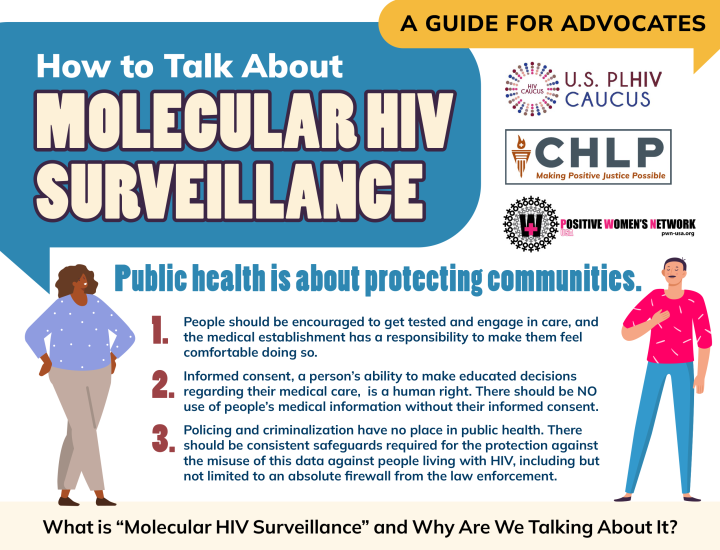

June 27 is National HIV Testing Day, and many of us spend the day raising awareness about HIV testing in the United States. Combating HIV stigma, making testing widespread and accessible, and affirming the right for people to test anonymously are essential to ending the HIV epidemic. However, reaching marginalized communities affected by HIV can only happen if medical providers and public health officials first build and maintain a bedrock of public trust. Trust is essential for public health since people will only connect with care if they feel safe. So why are state and local health departments engaging in trust-breaking endeavors like dangerous forms of surveillance, provoking condemnations from virtually every national HIV advocacy organization?

The Road to Violating Health Privacy

In 2018, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) introduced a new condition for HIV prevention funding at the state and local level: To receive funds, health departments were suddenly required to collect, analyze, and report HIV genetic data sequences created from drug resistance testing. Once someone is diagnosed with HIV, their medical provider will order an additional blood sample test. This test creates a unique genetic sequence of the virus, which is examined for mutations that might make it resistant to treatment.

Drug resistance testing is a routine part of care for people living with HIV and is ordered so doctors can best treat their patients. But now, that genetic data is reported to public health officials who use it for purposes that go beyond patient treatment. Thanks to the CDC’s funding requirement, this genetic data is now used to map the sexual and social networks of people living with HIV—a diverse and deeply stigmatized mix of communities—without their knowledge or consent. When HIV transmissions do occur, they are likely to take place through stereotyped and stigmatized activities, including through anal or condomless sex or sharing injection drug equipment. HIV evolves quickly―the disease progression takes route after 72 hours―which means public health officials can make inferences between similar strains of the virus, suggesting people are linked via direct or indirect transmission. The use of genetic data to map HIV transmission networks, reducing human beings to “clusters” where the virus is spreading, is called “molecular HIV surveillance.”

The CDC argues that molecular HIV surveillance enables them to better deliver traditional HIV care and prevention to the communities where they’re needed most. However, some public health officials have cast doubt about whether molecular HIV surveillance is ethical or effective. We know the communities left behind by efforts to end the epidemic experience hostility and discrimination while trying to access care within our flawed health system. Do we really need molecular surveillance, done without people’s consent or knowledge, to tell us Black and Brown people, immigrants, and queer and trans people are not getting the care they have a right to?

The Penalty for Living With HIV and Being Vulnerable to the Virus

Thirty states criminalize people living with HIV through either an HIV-specific law or a sentence enhancement that bumps a penalty level from a misdemeanor to a felony simply if the person charged is living with the virus. On top of that, half of all states use the general criminal law—from reckless endangerment and aggravated assault to even attempted murder—to criminalize people living with HIV. Data from the Williams Institute at the UCLA School of Law show that HIV-related prosecutions are not rare. Thousands, not dozens, of people living with HIV in the U.S. have made contact with and been singled out for punishment by our country’s dehumanizing, violent criminal legal system because of their HIV status.

For instance, more than 60% of people arrested for an HIV crime in Georgia were Black, and in Louisiana, 91% of arrests targeted Black men. In Florida, people were twice as likely to be convicted if they were also charged in the contexts of sex work, with Black women the most likely to face a conviction. A Black woman in Tennessee is 290 times more likely to be forced on the sex offender registry because of an HIV criminal conviction than a white man. In Missouri, there has been one HIV-related arrest of a Black man for every 43 Black men living with HIV.

The people confronted by barriers to HIV care, heightened stigma, discrimination, homelessness, poverty, and criminalization are the same people targeted because of their HIV status. Prosecutions in many states are not slowing down, and according to NASTAD, 33 states allow health departments to share HIV data in response to court or law enforcement requests. People living with HIV have raised the alarm about these issues for years, and for good reason: State health departments do cooperate in baseless and racist HIV-related prosecutions. These prosecutions have no place in our world. And medical and public health officials are within their rights to help stop them.

We Can Stand Up Against This

Think about the criminalization of self-managed abortion. Care providers, more than any other group, are responsible for alerting the police about people ending their pregnancies or about adults assisting people ending a pregnancy. Or let’s consider attacks on gender-affirming care. A hospital in Tennessee turned over medical records of transgender patients to the Tennessee attorney general.

People living with HIV often exist at the intersecting axis of various forms of violence―from classism and misogynoir to transphobia. Waiting any longer to stop the release of all forms of health data to law enforcement will intensify medical mistrust, reduce the likelihood of getting tested, threaten public health, and cost lives. The attacks against bodily autonomy and health privacy are deepened by a public health system unwilling to unequivocally condemn the use of health information for criminal punishment. It is within the power of health care professionals to demand that the CDC and other federal agencies protect all medical and public health data from being weaponized against people in prosecutions.

In the U.S., the vast majority of HIV arrests don’t require HIV transmission. Similarly, prosecutions overwhelmingly lack a requirement for the person charged to have even been capable of transmitting HIV. Arkansas’s law describes people living with HIV as “a danger to the public.” People across the nation have been criminalized while virally suppressed, meaning it’s impossible to sexually transmit HIV to a partner. Many have been criminalized for allegedly “spitting” at law enforcement, even though saliva cannot transmit HIV. Sex workers living with HIV face felony prosecutions for nothing more than initiating a conversation with undercover cops.

Criminalization is not rare. Health information, including HIV data, can be shared with law enforcement and used to punish people. Much like how HIV/AIDS activism shaped a generation of social movements fighting for LGBTQ rights, people living with HIV are setting a benchmark for our political moment today. The rights currently under attack, like bodily autonomy, sexual and reproductive freedom, and protections against the weaponization of health data, are foundational to the Denver Principles.

These values brought life to mass movements then—and can be an inspiration for our movement to dismantle racist policies that fuel criminalization. Groups like Interrupting Criminalization have created useful guidelines for health care providers to get this work started in your community. Outside of what is a bona fide medical necessity, it’s more clear than ever that we need health privacy protections to prohibit the release of any and all health information.