First Do No Harm: With cyberattacks on the rise, public health agencies must do more to stop the weaponization of our health data

Earlier this month, reports started to reveal a widespread breach of medical data stolen in a cyberattack targeting the Florida Department of Health (DOH). The hackers claimed to have 100 gigabytes of information, including private patient records, and threatened to publish it online if the DOH refused to pay their ransom. Because the Florida government doesn’t pay ransoms, the hacker group uploaded all its stolen files to the dark web.

The full extent of this breach may not be known for months or even years, but many believe it to be one of the worst hacking incidents in Florida history. According to a WFTV investigation in collaboration with cybersecurity experts, the hackers published more than 40,000 stolen DOH files on the dark web–twice the number of files initially reported.

Not every file published includes sensitive patient data. Some of the stolen materials are DOH flyers or maintenance records. However, many files do contain lab results, patient names and dates of birth, social security numbers, addresses, and insurance information. Everything from test results for foodborne illnesses to syphilis, hepatitis, and HIV is now accessible on the hacker group’s website.

This historic breach underscores what people living with HIV and activists at the frontlines of the struggle for privacy rights have been saying for decades: our health data isn’t reliably secure or protected. Health and public health organizations are the number one target for ransomware cyberattacks, according to a report published earlier this year by the Federal Bureau of Investigation. Medical records are a lucrative target for hackers because large health companies tend to pay ransoms, and in contrast with financial fraud, there are far fewer mechanisms to identify healthcare fraud.

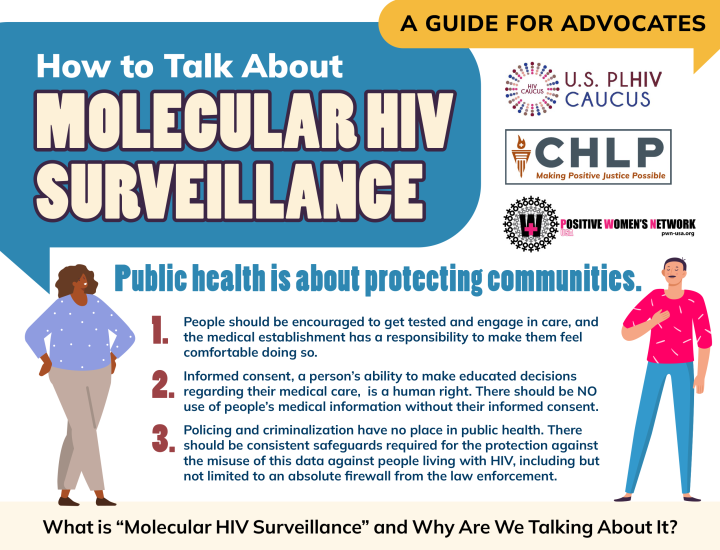

There’s nothing stopping people from finding these hacked DOH lab results. This breach could lead to someone’s HIV status being outed, a catalyst that may lead to criminalization. Despite the threat posed by cyberattacks, many health and public health stakeholders are simply not doing enough to stop sensitive, private medical data from being used against people in criminal prosecutions. The Florida DOH data breach highlights the concern advocates raised about state health departments being required to collect and store genetic data used to map the sexual and social networks of people living with HIV. Moreover, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) made states participate in the collection and storage of this data without first ensuring it could never be used to harm people in criminal prosecutions.

Florida has a felony law criminalizing people living with HIV, and an additional law used to punish sex workers living with HIV. We know that women accounted for over half of all HIV arrests in the state and that Black women were more likely to be convicted for an HIV-related crime in the context of sex work. People in Florida also face enhanced felony penalties for other crimes because of their HIV status and have been prosecuted under general laws, including attempted murder. The risk of criminalization is made all the more tangible since Florida law explicitly permits the release of DOH HIV information to the courts to be used in criminal prosecutions. Many other states have similar laws in place.

We can put an end to these harmful policies. We can stop the practice of allowing medical data, including HIV information, from being weaponized against people in criminal, civil, and immigration proceedings. To do that, we need the federal government and the CDC in particular to step up. Let’s stop holding “listening sessions” and start implementing incentives for states to change their laws that permit the release of health data to be used to prosecute people.

We can cut off the motives for hackers by halting the payment of ransoms in cyberattacks. We can demand better cybersecurity and fraud protections. But while criminalization endures as a threat to our people, we cannot allow public health agencies to ignore this form of state violence made possible by both their explicit policies and their carelessness.